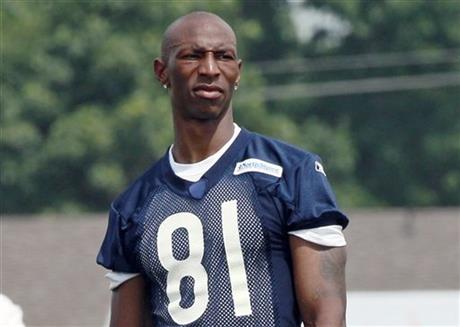

DALLAS (AP) — Once an NFL wide receiver and local hero with a $5 million contract, Sam Hurd was reduced to being a convicted felon in orange jail scrubs pleading with a judge to avoid spending the rest of his life in prison.

Hurd, 28, was sentenced to 15 years Wednesday for his role in starting a drug-distribution scheme while playing for the Chicago Bears.

He pleaded guilty in April to one count of trying to buy and distribute large amounts of cocaine and marijuana, which carries a maximum of life imprisonment. But U.S. District Judge Jorge Solis noted that the case against Hurd centered on a lot of agreements to buy and sell marijuana and cocaine, rather than physical transactions of drugs.

But, the judge said, You didn’t just start nickel and diming it.

Hurd stood before him in orange jail scrubs after a rambling, emotional 30-minute plea for mercy. Behind him in the gallery were more than a dozen family members and friends.

At the start of the hearing three hours earlier, Hurd had walked into the courtroom carrying handwritten notes. But he often strayed from those notes, looking directly at Solis with his hands grasping a lectern in front of him. At times, he tried to go point by point through the allegations against him, explaining his dealings with co-defendants and others accused of helping him buy drugs.

I just know that my life depends on everything that’s going on in here right now,” Hurd said.

Authorities say that while NFL teammates and friends knew him as a hardworking wide receiver and married father, Hurd was fashioning a separate identity as a wannabe drug kingpin with a focus on “high-end deals” and a need for large amounts of drugs.

Hurd denied being a kingpin, but said he was a marijuana addict with a penchant for trusting friends and saying things he didn’t mean.

I have regrets, your honor, Hurd said. I have a lot of regrets.

His biggest regret was starting to smoke marijuana, an addiction he said he picked up in college at Northern Illinois and that grew once he got to the pros. Hurd has claimed he shared marijuana with former teammates and smoked every day during parts of his career with the Bears and Dallas Cowboys.

I made some dumb, very bad decisions, Hurd said.

Hurd’s December 2011 arrest outside a suburban Chicago steakhouse came after he tried to buy a kilogram of cocaine in what turned out to be a sting. According to a federal complaint, Hurd told an undercover agent that he wanted 5 to 10 kilograms of cocaine and 1,000 pounds of marijuana per week to distribute in the Chicago area. He claimed he was already distributing 4 kilograms a week, according to the complaint. A kilogram is about 2.2 pounds.

At the time, Hurd was a wide receiver with stints for the Bears and Cowboys who had played most of his five seasons on special teams. He was in the first year of a three-year contract reportedly worth more than $5 million.

“You had everything going for you, Solis told Hurd, adding that he thought the case was a tragedy.

In the end, Solis gave Hurd a much shorter sentence than the 27 to 34 years recommended by federal sentencing guidelines. There is no parole in the federal system, though inmates can typically apply for early release after serving 85 percent of their sentences.

The Bears cut Hurd after his arrest. He was released on bail and returned to Texas, where he grew up, but soon fell into trouble again, according to court documents. He allegedly tried to buy more cocaine and marijuana through a cousin, Jesse Tyrone Chavful, and failed two drug tests. That led a magistrate judge in August 2012 to revoke his bail and order him returned to jail.

While he denied leading a major conspiracy or dealing with Chavful, Hurd admitted to giving $88,000 to another co-defendant, Toby Lujan, knowing that the money might go to buy drugs. He also admitted the fateful meeting at a steakhouse that ended in his arrest.

His attorneys tried to explain his claims of having high-value customers and massive demand for drugs as mere boasting, saying he had a penchant for exaggeration. One of his lawyers, Michael McCrum, called Hurd “a guy showing up at a restaurant, talking stupid.

I think he should be punished, but for the crime that he committed, McCrum said.

But Hurd’s failed drug tests and alleged dealings with Chavful appeared to factor heavily against him Wednesday. Prosecutors repeatedly brought up Chavful — rejecting claims by Hurd and his attorneys that the two men were talking about Hurd’s attempts to start a T-shirt printing business.

Normally, when you dig a hole, you quit digging, said prosecutor John Kull. But he keeps digging.

Chavful and Lujan have both pleaded guilty to being involved in the conspiracy. Solis gave Chavful eight years in prison for his smaller role in the scheme. Lujan will be sentenced in January.

While Hurd gained extra notoriety due to his now-finished football career, prosecutors said his case was simple.

He’s not being prosecuted because he’s an NFL player, Kull said. “He’s being prosecuted because he’s a drug dealer.

___

Follow Nomaan Merchant on Twitter athttp://www.twitter.com/nomaanmerchant .