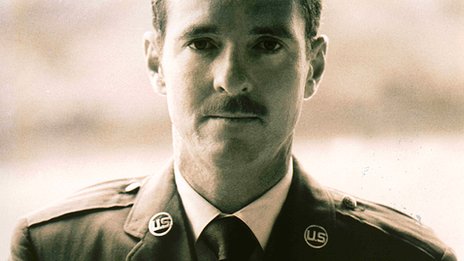

In 1975 an air force sergeant made history when he came out, to challenge the ban on homosexuals in the US military. Leonard Matlovich became a figurehead for gay rights, but he could not have foreseen that in 2013 the US Supreme Court would be considering whether to overturn a ban on same-sex marriages.

“It just tears me apart on the inside,” Matlovich said in his first national TV interview in May 1975. “My conscience just wouldn’t let me do it any more. I had to come forward and say: No more, America!”

Matlovich was the kind of serviceman the air force prided itself on. He had voluntarily served three tours of duty in Vietnam. He had been injured while clearing landmines and was awarded a Purple Heart and the Bronze Star medal.

At the time, David Addlestone was working as a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union and had been looking for a gay soldier who would put himself forward to challenge the ban on homosexuals serving in the military.

“He was the perfect test case,” says Addlestone, who hoped Matlovich’s excellent military record might make the air force think twice about applying the ban.

Addlestone warned Matlovich, nonetheless, that he was likely to be discharged and “throw away 13 years of military service and a pension”. But “Leonard said he couldn’t live a lie” any longer, Addlestone recalls.

Matlovich had only come to terms with his homosexuality two years earlier, at the age of 30. Both his parents were deeply religious and politically conservative – his father had also served in the air force – and Matlovich was a devout Catholic himself.

“We were very much a ‘What do the neighbours think of me?’ type of family,” says his niece Vicky Walker. “We had to do everything the right way. We were not even allowed to drink soda. My grandfather was very strict – loving but strict.”

According to Michael Bedwell – a gay rights activist who became a close friend and flatmate for several years – Matlovich knew from an early age that he was “different”.

“He was self-loathing primarily because of his religious and conservative upbringing,” says Bedwell.

“Leonard even admitted to me that one of the reasons why he had kept on volunteering for Vietnam was because he had a subconscious death wish – suicide by war… thoughts he regretted very much later.”

Bedwell says it was only when Matlovich started visiting gay bars and meeting positive gay role models, such as a lesbian bank executive, that he finally came to terms with his homosexuality.

“He started meeting people who were different to the stereotypes he grew up with, people who were contributing to society,” says Bedwell.

Matlovich had accepted that he was gay, but he had not come out except to a close circle of friends, not even to his own family.

By that time, Matlovich was working as a race-relations instructor in the air force, a role introduced in response to the civil rights movement.

“In Vietnam he had met black soldiers and started questioning the racism he grew up with,” says Bedwell, who believes these experiences prompted Matlovich to come out to his superiors.

“Leonard had been taught that the United States was the land of the free,” says Bedwell. “He realised that in the same way our country had once been wrong in denying those freedoms to people of colour, it was wrong to deny them to gay people.”

Matlovich wrote a letter to his commanding officer, revealing his homosexuality and asking for an exception to be made because of his service record.

The officer “looked at it and said: ‘Just tear it up and we will forget it.’ But Leonard refused,” remembers Addlestone.

The air force responded by starting a discharge procedure.

Bedwell says Matlovich had by then come out to his mother, who had pleaded with her son not to tell his father, out of fear he would blame her. “She thought she had done something wrong,” says Bedwell. “She encouraged Leonard to see a psychiatrist.”

But Addlestone wanted to make the case public, so in 1975 on Memorial Day – a day of remembrance for those who have died in US service – Matlovich gave an interview to the New York Times.

An interview on CBS TV news was to follow that evening, so Matlovich decided to come out to his father, but when he called home, his father had already found out from the media.

“His father’s reaction was very emotional,” says Bedwell. “He went into the bedroom and cried. But he came out and said: ‘If he can take it. I can.'”

More interviews followed and in September 1975, just before the discharge hearing was to start, he became the first openly gay person to appear on the cover of Time magazine, declaring: “I am a homosexual”.

“He had become a poster boy for gay rights,” says Bedwell. “He became a hero particularly to those in the military. I remember where I was when Kennedy was assassinated and I remember where I was when I saw when Matlovich was on Time magazine.”

Addlestone says Matlovich’s media appearances had a big effect on America. “He was a patriotic, conservative middle-class war hero. He destroyed the popular myth of homosexuality.”

Bedwell adds: “He was very unassuming, not the stereotypical homosexual.”

Matlovich was soon ruled unfit for service. He was recommended for a general, or less-than-honourable discharge, but eventually granted an honourable one.

He appealed and five years later, following a protracted legal process, a judge ordered that Matlovich be reinstated and promoted. The air force offered Matlovich a financial settlement and, convinced they would find some other reason to discharge him if he re-entered the service, he accepted.

Addlestone says members of the gay community had urged Matlovich to go back to the air force, so this was a tough choice to make.

Matlovich got involved in other gay rights causes and opened a restaurant. Addlestone says his former client also attracted what he calls gay groupies. “People wanted to hang out and have sex with him,” he says.

In 1986 he was diagnosed as being HIV positive. The following year he made a second startling public statement, revealing during a TV interview that he had the condition.

“I saw him in Washington DC when he was dying of Aids,” Addlestone says. “He had no regrets – had reconciled with this father – the only problem he had was that he was a celebrity. He was very much a humble human being.”

He died in June 1988 – 25 years ago, all but a few weeks.

His gravestone at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington bears the inscription: “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”