NEW YORK (AP) — By the time a wayward kid from the New York City suburbs named Bryant Neal Vinas joined al-Qaida in 2008, the sight of trainees swinging from monkey bars was a thing of the past.

The Afghan terror camps had been replaced by safe houses tucked away in the border region of Pakistan — houses made of mud. “There’s no carpet. There’s no wood floors,” Vinas told a Brooklyn jury on April 23. “Just mud.”

Vinas’ description of the crude Waziristan hideout came during the trial of Adis Medujanin, a New York City man convicted last week in a foiled plot to attack the New York City subway system in 2009. Prosecutors had accused Medunjanin of receiving terror training and instructions from al-Qaida in Pakistan during a trip with two former high school classmates who pleaded guilty.

At Medunjanin’s trial, jurors heard Vinas and another high-value government cooperator born in Great Britain, Saajid Badat, testify as expert witnesses. They provided an unprecedented, firsthand look at al-Qaida in the heady days following the Sept. 11 attacks and in more recent years as it struggled to survive.

The pair’s insights suggested that the terror group never lost its desire to strike again on U.S. soil but its means and goals became more modest. It also became more reliant on late-bloomer jihadists who sometimes proved half-hearted or inept.

The testimony also gave the U.S. attorney’s office in Brooklyn and British authorities a chance to show off two trophies in the civilian prosecution of terrorists — sworn enemies of America who, after their arrests, were persuaded to switch sides and tell everything they know.

Badat, 33, described growing disillusioned with al-Qaida. After hearing that admitted Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed would face American justice, he said he “felt … almost a moral obligation to give evidence specifically against KSM.”

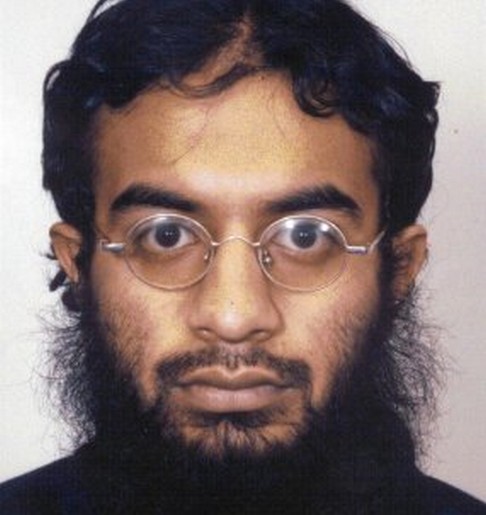

The once-bearded Badat appeared on a videotape looking like a clean-cut banker. His testimony had been recorded at a secret location outside London after he was freed early from a 13-year prison term as a reward for his cooperation.

Born in Gloucester, England, to immigrants from the tiny African nation of Malawi, Badat was the product of a stable childhood. He attended respected schools while playing soccer and rugby. Prodded by his father to become an imam, he memorized the Quran by age 12.

His aspirations turned violent when he learned more about the oppression of Muslims in Bosnia. While in London in 1997, he became convinced he needed to take up arms in the name of Islam. “It was almost the glamour factor of it drawing me in,” he said of heading off to Afghanistan at age 19 for “violent jihad.”

By 2001, he was firmly in al-Qaida’s grasp at the height of its post-Sept. 11 infamy. He recalled Osama bin Laden telling him in a meeting of just the two of them that hiding explosives in shoes in suicide attacks could get huge results.

“So he said the American economy is like a chain,” Badat said. “If you break one link of the chain, the whole economy will be brought down.” The highest ranks of al-Qaida, including Khalid Sheik Mohammed, picked him and Richard Reid for a shoe bomb plot in September 2001. Reid was caught aboard a plane in December with explosives; Badat backed out.

His reluctance was based on “my fear of performing the mission and also the fear of … the implication for my family,” he said. Vinas, 29, was the offspring of immigrant parents, both from South America, who divorced when he was young. As time passed, he drifted. He also tried joining the Army in 2002, but dropped out after only three weeks because he found it “mentally overwhelming.”

Raised Catholic in Long Island, east of New York City, Vinas converted to Islam in 2004. He grew more extreme in his views after listening to sermons by radical anti-American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. Vinas left for Pakistan in 2007, telling friends and family he was going to study there. He briefly signed on with a little-know insurgent group, but left after hearing rumors it was controlled by Pakistan’s intelligence agency, known as the ISI.

“I didn’t want to do ISI’s dirty work,” he said. Eventually, Vinas was recruited by al-Qaida operatives in 2008 and spirited away to the mud structures akin to a one-room school house with not enough books to go around. He was given weapons training with strict limits on how many rounds he could fire — 30 from an AK47, 20 from a machine gun and only six from a Soviet-era pistol.

When not praying, Al-Qaida teachers also showed recruits how to “make a sandwich” out of plastic explosives and ball bearings so they could be fitted into a suicide vest, Vinas said. His reasons for becoming a suicide bomber were practical more than anything else.

“I was having a difficult time with the altitude. I was getting very sick, so I felt that it would be easier to do a martyrdom operation,” he said. As Vinas began to meet higher-ranking members of al-Qaida under the command of Saleh al-Somali, the network’s former chief of external operations, he caught their attention by suggesting that the Long Island Railroad — a commuter rail system he knew by heart — would make a ripe target for an attack, using a suitcase full of explosives left on a train. He also pitched the idea of blowing up a Walmart by buying a television, rigging it with a bomb and returning it to the store.

His handlers concluded the bombers should “be a white man from one of the Western countries, with Western documents,” Vinas testified. The goal, he added, was to “cause a very big economic hit.” Was another goal to kill as many people as possible?

“Yes,” he said.