(Reuters) – The festering economic crisis in Europe could help determine the outcome of the U.S. presidential election, but don’t expect President Barack Obama or his Republican rival, Mitt Romney, to spend much time talking about it.

The November 6 election is widely expected to turn on the state of the U.S. economy, and the impact of Europe’s slow-motion meltdown has begun hitting Wall Street, manufacturers and other businesses. U.S. households have lost $1 trillion in wealth since March as the euro zone crisis has pushed stock markets down, according to JP Morgan.

Any number of scenarios, from a Greek exit from the euro currency to a run on Spanish banks, could spark a financial crisis that would recall the dark days of 2008.

Ideally, elections provide an opportunity for candidates to tell voters how they would handle such a potential calamity. But Obama and Romney have barely mentioned the euro zone crisis since a slew of disappointing economic indicators pushed Europe’s woes to the fore last week.

After Friday’s dismal jobs report, Obama cited “headwinds” from the euro zone, before returning to his familiar complaint about how Republicans in Congress are blocking his job-creation proposals. Romney said Europe was having a “dampening effect” on the United States, but said Obama has made the nation more vulnerable to outside disruptions.

They’re not likely to discuss the topic in much detail in the weeks ahead, analysts say, even as Obama’s administration pressures European governments to move toward a tighter fiscal and financial union.

For both candidates, the risks of dwelling on Europe’s financial problems simply outweigh the possible benefits.

Obama could look powerless if he draws voters’ attention to a situation largely out of his control. He also could undercut his argument that industrial Midwestern states have benefited from his bailout of the auto industry if he talks about the slowdown in exports.

Romney, meanwhile, could undermine his argument that Obama has mishandled the U.S. economic recovery if he tries to blame the president for decisions that have been made in Berlin, Paris and Athens.

He also must avoid the perception that he is cheering for bad economic news, even if it would boost his prospects in November.

“Neither of them are talking about it, and they won’t,” said David Gordon, research director at Eurasia Group, a risk-consulting firm. “Obama can’t, because he’ll look impotent, and Romney doesn’t want to because he’d be giving Obama an out” in taking responsibility for the U.S. economy.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES?

That means both presidential candidates are leaving compelling arguments on the table.

Obama could claim some success on the diplomatic front.

Pressure from his administration may have helped to trigger moves by European officials to step up their scrutiny of vulnerable banks, propose backing off steep spending cuts, and consider policies that would knit the 17 euro zone countries closer together.

Europe’s woes have deepened after several years of sharp spending cuts, and Obama could make the case that the same thing could happen in the United States under the steep cuts advocated by Romney and his fellow Republicans.

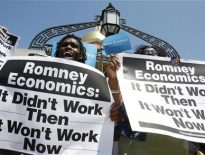

One prominent Obama ally has made that case.

“The Republican Congress and their nominee for president, Governor Romney, have adopted Europe’s economic policies,” former president Bill Clinton said at a fundraiser for Obama in New York on Monday. “Their economic policy is austerity and unemployment now, and then a long-term budget that would explode the debt when the economy recovers so the interest rates would be so high, nobody would be able to do anything.”

If Obama himself were to link Romney’s policies with those in Europe, he could alienate European leaders at a time when he is working with them to contain the crisis.

“As president, he really can’t be directly criticizing his colleagues in Europe,” said Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Southern Methodist University. “He must treat them diplomatically.”

Obama has not been totally silent on the crisis.

After a G8 summit at Camp David two weeks ago, the president said that Europe must inject capital into its banks, adopt a strategy to spur economic growth, use monetary policy to help countries such as Italy and Greece implement austerity measures, and continue fiscal discipline.

On Monday, White House spokesman Jay Carney pressed Europe to take more steps to ease investors’ concerns. Treasury undersecretary Lael Brainard, the administration’s point person on the European crisis, said on Tuesday that the United States expects euro zone countries to strengthen their fiscal and financial ties.

In recent days, Obama hasn’t gone much beyond acknowledging that Europe’s problems have reached across the Atlantic.

“The crisis in Europe’s economy has cast a shadow on our own,” he said in a Saturday radio address.

ROMNEY’S FOCUS: OBAMA, NOT EUROPE

For Romney, Europe’s woes could be used to illustrate the perils of big government.

Rigid labor laws have hurt Spain’s ability to recover from its housing bubble, while generous public-sector salaries and pensions have driven Greece’s debt load to unsustainable levels, for example.

Rather than focus on such matters, Romney has steered the discussion back to Obama’s stewardship of the domestic economy.

“Developments around the world always influence our jobs, but we should be well into a very robust recovery by now,” Romney said on CNBC on Friday.

“If the president’s policies had worked, if he had been able to get America back on track, we would be looking at what happened in Europe as being a problem, but certainly not devastating.”

Any specific proposals Romney offers on the euro crisis could come back to haunt him if he wins the White House. Not only could they alienate foreign heads of state, but they could provide ammunition for political foes at home.

Much as Romney’s campaign has hammered Obama for his overly optimistic projection in early 2009 that unemployment would not rise above 8 percent, any solutions floated by Romney could be resurrected by Democrats if they don’t pan out.

Romney and his fellow Republicans also must deflect Democratic claims that they are cheering signs that the economy is stalling.

“Although they do believe continued struggles of the American economy” benefits them, Jillson said, “it doesn’t mean they’re clapping.”

(Editing by David Lindsey and Will Dunham)