KINGSTON, Jamaica (AP) — Black-clad police toting submachine guns entered the slum of narrow streets lined with wooden shacks and crumbling concrete buildings in Jamaica’s capital. As usual, they were looking for fugitives, drugs and guns. But this time, they were also after a different quarry, one they say has a no less corrosive impact on society.

The force descended on bright, intricately painted murals and graffiti scrawls celebrating leaders of Jamaica’s violent underworld. With rollers and paint, the officers erased images of gang strongmen known as “dons,” who have long been hailed as latter-day Robin Hoods by poor residents of the slums. Also slated for removal were murals of lesser-known gunmen memorialized where their bodies fell.

As shirtless young men looked on, the police were hoping to beat back the lawless culture that has defined the gang-steeped area for decades. In slums across Jamaica, but particularly in West Kingston, the aerosol artistry starkly highlights the influence of drug-and-extortion gangs that have long driven Jamaica’s eye-popping violent crime rates. Since 2009, Jamaica’s bloodiest year on record, curfews in hotspots and an aggressive anti-gang crackdown have steadily reduced the homicide rate. Still, the island of 2.7 million people has seen 1,000-plus killings every year since 2004, giving it one of the highest murder rates in the hemisphere.

In recent years, the government has asserted its presence in slums such as West Kingston, with the anti-mural effort only the latest sign of the campaign. The tug-of-war for the hearts and minds of slum dwellers began after security forces killed at least 76 civilians in a 2010 siege while hunting for second-generation “Shower Posse” gang boss Christopher “Dudus” Coke, whose criminal empire seemed untouchable until the U.S. demanded his extradition.

Still, more than three years later, many West Kingston residents consider the dons cultural touchstones and speak about them with pride. They complain that authorities are trying to erase history by painting over the murals commissioned by the gangs.

“These pictures are part of our memories. The dons have always been a big part of life here. It’s not like anybody can just get some paint and make our traditions different,” said Patrick Jemson, a middle-aged resident of Tivoli Gardens, the backbone of the Shower Posse’s longtime slum fiefdom.

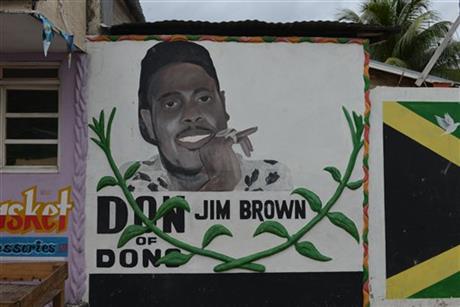

The crime boss most often glorified on the streets is Coke’s father, Lester Lloyd Coke, better known as Jim Brown, whose ruthless syndicate was responsible for 1,400 killings on the U.S. East Coast, according to the FBI. One of the few remaining murals of Brown, who died in a mysterious jail fire in 1991 while awaiting extradition to the U.S., remains on a wall next to a casket shop in the troubled Denham Town slum. Below his face, a local artist has declared him the “don of dons.”

“He was a world boss,” said a teenage boy who would only give his name as Oneil as he looked hard at Brown’s grinning image.

Powerful, politically connected dons ruled West Kingston’s slums, which were used by political leaders at election time when intimidating gang henchmen rustled up votes for both of Jamaica’s main political parties. The dons enforced a fearsome discipline while supplying groceries to families in need and paying pensions to the kin of fallen “soldiers.”

Police Superintendent Steve McGreggor, who took over leadership of the tough West Kingston police division last month, said that culture is changing and vowed to erase every painted image paying respect to gangsters.

“I’ve issued a warning to people that if any of these communities puts them back up and defies this new development they will feel the wrath of the police,” McGreggor said.

The superintendent added that he plans to encourage residents to replace gang images with murals of high-achieving students or athletes from the neighborhoods. He’s also quipped to slum dwellers that they could even paint his likeness on a wall in another year if he brings order to the area sometimes referred to as the “wild, wild West.”

The effort comes as police report that feuds over “donmanship” in the area have intensified. A dispute pitting members of the Coke clan against relatives of former strongman Claude Massop flared up in recent weeks, but police say they have since brought it under control.

Rivke Jaffe, an anthropologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who has conducted extensive fieldwork in Kingston, said the murals are only one among many elements legitimizing don authority to residents.

“A lot of their authority has to do with the things they offer residents that the state does not,” Jaffe said in an email.

In bullet-pocked Tivoli Gardens, unemployed laborer Ernest Rennie said he’s confident painting over the murals won’t change attitudes until the Jamaican government delivers more services and opportunities to slums where joblessness is pervasive.

“The government has never treated the people here fair, and the old lions and the young cubs know it,” Rennie said from his spot on a curb. “With Dudus gone, things are harder now.”

Although Coke was Jamaica’s biggest gang leader, no murals depict the pot-bellied, 5-foot-4-inch Jamaican dubbed “president” by his followers. He may have looked unassuming, but U.S. authorities said he was one of the world’s most dangerous drug lords before his capture in 2010, controlling a network of large-scale drug dealers in the U.S. and trafficking illegal guns into Jamaica.

Plenty of streetside scrawls around Tivoli Gardens vow allegiance to him and his father, a sign that authorities are in for a long fight. A wall on one corner declares: “Dudus 4 life.”

___

David McFadden on Twitter: http://twitter.com/dmcfadd