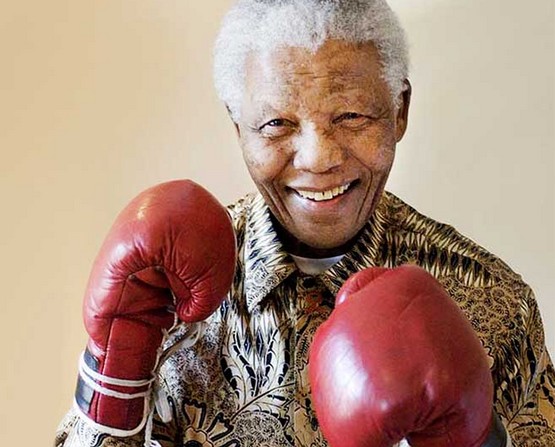

Nelson Mandela died one year ago around this time.

Everyone already knows Nelson Mandela was a fighter. That will be obvious to those that are above ground and all those that come after us. He was also, perhaps not so coincidentally, a boxer.

In his autobiography, The Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela’s affection for the art of pugilism is made plain:

“Boxing is egalitarian. In the ring, rank, age, color, and wealth are irrelevant . . . I never did any real fighting after I entered politics. My main interest was in training; I found the rigorous exercise to be an excellent outlet for tension and stress. After a strenuous workout, I felt both mentally and physically lighter. It was a way of losing myself in something that was not the struggle. After an evening’s workout I would wake up the next morning feeling strong and refreshed, ready to take up the fight again.”

Mandela was very honest about his own skills as a boxer.

“Although I had boxed a bit at Fort Hare, it was not until I had lived in Johannesburg that I took up the sport in earnest. I was never an outstanding boxer. I was in the heavyweight division, and I had neither enough power to compensate for my lack of speed nor enough speed to make up for my lack of power.”

However, the resilience and strategy Mandela learned from the sport of boxing would serve him well over the rest of his life, and particularly through the most difficult times he would soon be facing.

As the leader of the African National Congress, Mandela stood up to the practice of Apartheid that the black minority suffered under in South Africa. As a young man, he was considered a radical. In 1948, Mandela co-founded an armed group within the African National Congress that took part in the bombing of South African government targets in 1961. Of course, under the sort of oppression that the native population was suffering from, one could argue that it was understandable. We were living in a democratic utopia in 1776 compared to what the black South Africans were going through during Apartheid and no one in our history books begrudges us our rebellion.

In 1962 Mandela was arrested and charged with conspiracy. He spent the next 27 years of his life in prison, 18 years of it in a small cell on Robben Island. The diminutive space of his confines were dramatized in Clint Eastwood’s fine film, Invictus in 2009. The Rugby player depicted in Invictus by Matt Damon walks into an actual Robben Island cell and extends his arms and finds that the walls barely extend beyond his wingspan.

Mandela changed while incarcerated. His convictions remained every bit as strong, but the militant nature of his former outlook was replaced by something else, something more…graceful. He became the leader of his fellow African National Congress prisoners and achieved certain reforms, such as receiving pants and being able to play games. I suppose that sounds small, but considering the iron fist that the country was being ruled with at the time, I’m sure any accommodations made life just a bit more bearable. He also studied Christianity, Islam, and learned the language of his captors, Afrikaans, in an effort to forge bonds with the prison guards.

Still, the conditions were horrible. Verbal and physical abuse was typical. His eyesight was permanently damaged by the lime quarry in which he was forced to work. His cell was not only small, but damp. He slept on a bed of straw. He eventually developed tuberculosis. A condition that dogged his lungs for the rest of his days.

Despite his remote location, Mandela became a symbol of hope to his native countrymen. Other activists looked to his words and deeds and found inspiration in them. The outside pressure on the South African government to release Mandela became enormous. In 1988, due in part to his diminished physical condition as well as international pressure, Mandela was moved to a much more humane location for the remainder of his imprisonment.

In 1989, conservative, F.W. de Klerk, took over as the President of South Africa after the previous leader, P.W. Botha, suffered a stroke. de Klerk believed that Apartheid was an unsustainable form of government and soon released all ANC prisoners, save one. Nelson Mandela. However, de Klerk did take a number of meetings with Mandela and was significantly charmed by the imprisoned activist and soon released him.

Then things got really interesting.

One might think that after enduring such inhumane conditions for so long that Mandela would have departed from prison with bitterness and anger. And let’s be clear, Mandela is not so saintly as to not have experienced those feelings. What he understood that so many others would have not is that the holding of those emotions was essentially a second prison and would lead to no healthy resolution. Instead, Mandela continued to meet with de Klerk to discuss how to wind down Apartheid and remake their nation. Ever so crafty, Mandela also reached out to other world leaders, creating allies and maintaining visibility for his movement. In 1991, de Klerk and Mandela agreed to a peace accord against the backdrop of boiling violence inside their nation that threatened a civil war.

Mandela soon became the leader of the ANC and over the next three years, he and de Klerk managed to keep the country on the precipice of disaster without going over. During this time, Mandela negotiated the release of all political prisoners, the creation of a constitution and a Bill of Rights, as well as a constitutional court. Mandela embraced business interests (which were controlled by whites), and moved away from the nationalistic fervor held by many of his constituents. Both moves were deeply criticized by those that followed him, but Mandela was playing a long game.

South Africa finally held a democratic election in 1994. The minority white population was terrified at the possibility of a native President. Would that person not seek revenge? What would become of their lives? They would soon find out. Mandela won the election to become the President of South Africa with 62% of the vote.

That was the easy part.

Mandela now had to bring together a nation of the oppressed indigenous majority and the privileged white minority. How could this be done? Neither side trusted the other, and who could blame them? Most whites lived in nice houses and had all the advantages of power. The native population lived in tin shacks in shanty towns and lacked any upward mobility. To say the least, tensions were high.

Mandela saw a national reconciliation movement as the only way forward. He met with the former leaders of the Apartheid regime, supported the national rugby team which had been seen as a symbol of oppression, and most significantly, created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The purpose of the commission was not only to investigate crimes committed during Apartheid, but also–in a move that can only be considered revolutionary–created a process that traded amnesty for confessions. Amazingly, the bulk of the nation accepted the policy and a peace beyond possibility was achieved.

Mandela stepped down from the presidency in 1999. When good health permitted, he continued to be a symbolic and actual force for justice. Meeting with him became almost a rite of passage for other world leaders. He became the rarest of things, a humble giant.

So what does any of that have to do with boxing? Perhaps Mandela’s own words will explain it more simply than I:

“I did not enjoy the violence of boxing so much as the science of it. I was intrigued by how one moved one’s body to protect oneself, how one used a strategy both to attack and retreat, how one paced one’s self over a match.”

Nelson Mandela spent 27 years getting knocked down, and when he was finally able to get himself into a position to take advantage of the weakness of his opponent, his approach was both artistic and scientific. He moved forward, backward, from side to side. He outworked and outlasted those that would take him down and keep him down. When the bell rang, he answered it. Every single time. I wonder where he learned that?