(Reuters) – It was not so long ago that Bashar al-Assad’s enemies thought he was finished.

In the summer of 2012, the rebels were not just at the gates of Damascus, but inside the capital, preying on Assad’s harried forces.

His government had lost big chunks of Syria’s territory and a string of strategic towns, and a small number of loyal and tested army units were rotating around the country in an exhausting attempt to hold back rebel advances on many fronts.

Not any longer.

Now, even as the United States seeks to increase aid and training to moderate rebels to fight Assad’s forces, U.S. officials privately concede Assad isn’t going anywhere soon.

Buoyed by a sequence of victories over the past year, won in large part through Iran and Hezbollah, its Lebanese paramilitary proxy, Assad will be elected president this week for a third seven-year term, symbolically contested by selected opponents playing walk-on roles to pad out the main drama.

The old Syria – at its core a security state run by the Assad clan, their Alawite allies and selected partners from other minorities and the Sunni majority – is reasserting itself.

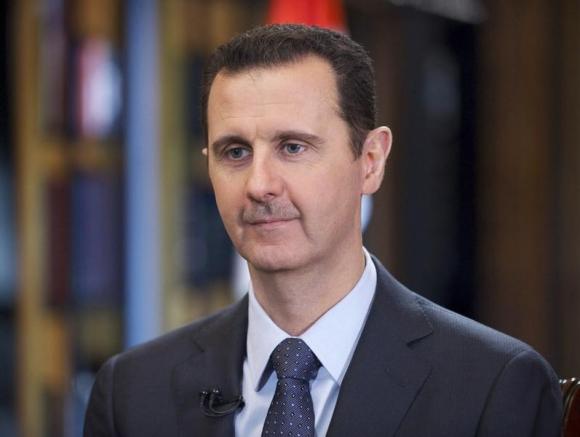

Assad himself, who had almost dropped out of sight and, on the rare occasions he did appear in public, looked troubled and strained, has re-emerged looking relaxed, confident and smart as he gets out and about, campaigning with his wife, Asma.

TRIUMPHALISM

There is a note of triumphalism when he speaks, a sense that the tide of the crisis, that began as a popular revolt against his rule, has turned in his favour.

Despite the loss of 160,000 lives and the displacement of 10 million Syrians, the shattering of cities like Homs and Aleppo and wholesale destruction of infrastructure and the economy, Assad proclaims Syria will become again what it once was.

During a visit to the ancient Christian town of Maaloula on Easter Sunday, after it had been recaptured from rebels, he told soldiers: “We will remain steadfast and bring security back to Syria and defeat terrorism. We will hit them with an iron fist and Syria will return to how it was.”

“The battle may be long but we’re not afraid; Syria has been like that all its life, he said on another stop at nearby Ain al-Tina. “As long as we’re together…we’ll rebuild it. However much they destroy we will rebuild and make it even better.”

Such is his confidence that he is contemplating retaking the whole country after the presidential election, according to a Lebanese political ally who sees him regularly.

Having regained control of a chain of cities up the north-south backbone of the country, secured his grip on the north-west coast and Alawite heartland, and cleared rebels away from Lebanon’s border, he is mulling a new offensive against Aleppo, before pushing right up to the northern frontier with Turkey.

According to the Lebanese ally he would leave parts of eastern Syria that are connected to the insurgency in western Iraq under the control of al-Qaeda-linked jihadis – fitting Assad’s contention he is fighting foreign-inspired terrorists.

This would also send a warning to Western and Arab supporters of the mainstream rebels that getting rid of him opens the gate to Sunni extremists.

REASSERTING CONTROL

Diplomats close to Assad acknowledge that part of his strategy has been to overlook the presence of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), an al-Qaeda division led by foreign jihadists, who have been fighting the moderate rebels – the first to rise up against the Syrian leader’s rule.

It’s a logical strategy. Why attack ISIL if ISIL is attacking your enemy?, one Arab diplomat said.

But Assad will eventually retake even the east, the Lebanese ally confidently predicts, citing the Algerian state’s long and bloody campaign to eradicate Islamist insurgents in the 1990s.

It will take time but Algeria lasted seven to eight years until the government purged the country and regained control, he said.

Yet, seductive though this scenario may be to the loyalist camp, Assad has returned from the brink only because powerful foreign allies – Iran, Hezbollah, and Iranian-trained Iraqi militias on the ground and Russia in the UN Security Council – have intervened decisively as the US, Europeans and Arabs have mirrored the indecision and muddle of Syria’s rebel opposition.

Assad has not won, Assad has survived, says Fawaz Gerges, a Middle East expert at the London School of Economics. There is a big difference between weathering the violent storm and basically defeating the opposition.

Both in his discourse and his image he projects much more confidence, he is much more at ease, he projects a narrative of victory, Gerges says. The truth is that al Qaeda has damaged the opposition and has strengthened Assad’s hand.

But the fact is the opposition is divided but not defeated yet. You have between 70,000 and 100,000 fighters and we have to wait and see how the opposition, and how the United States, Western powers and regional allies play their cards.

PYRRHIC VICTORY?

Lebanese columnist Sarkis Naoum, a Syria expert who from the start predicted a long conflict, says Assad has won the first half of the conflict. It is a pyrrhic victory. The scale is on Bashar and Iran’s side now but for sure Bashar won’t be able to win the overall war.

While there are indications that the U.S. and its allies are beginning to worry more about an al-Qaeda revival in Syria than about removing Assad, Western diplomats say, there is also evidence Washington is encouraging Saudi Arabia to provide selected rebel units with more sophisticated anti-tank weapons and Qatar to upgrade their skills with military training.

U.S. President Barack Obama, facing criticism that he has been passive and indecisive on Syria, said last week that he would work with Congress to ramp up support for those in the Syrian opposition who offer the best alternative to terrorists and brutal dictators but he offered no specifics.

While Obama and Congress deliberate, the dominant fear remains the absence of a credible alternative to take over power from Assad, whose family has ruled Syria ruthlessly for over 40 years. Instead, they see a scenario under which the country of 23 million people may go the way of Iraq or Libya.

At home, Assad is fond of telling foreign journalists that he and his wife continue to move around Damascus freely and without personal security. But locals say that has not happened since the uprising erupted in March 2011.

Security surrounding Assad’s movements is so tight that even at official ceremonies, it is not clear if the footage shot is of the same day or a previous day, they say.

One close observer noted that Assad doesn’t tell his guards in advance about his movements. He suddenly emerges and they run after him to follow movement orders on the spot, he said.

CLOSE TO HOME

Mortars continuously hit close to Assad’s private residence in Damascus, residents who live in the area say.

During a recent mortar barrage that came unusually close to his residence, neighbours say they saw several cars with darkened windows leave from a basement.

It was so fast, almost instantaneous. We heard the mortar blast, which we felt in our home. It shook our windows. And by the time I walked up to the window to see what was happening, I saw maybe 10 cars leave from his residence, one after the other, all of them in a big hurry, one resident said.

Locals along the Syrian coast say Assad and his family have not been to their summer residence for at least two years.

Western diplomats say that about a year into the uprising, Assad must have gotten advice from his friends not to leave Damascus as it is the ultimate prize for the rebels.

Under all scenarios, experts say a military solution to oust Assad is out of the question and, barring an assassination, a nuclear deal between Iran and major powers could in the long-term be the only way forward to usher a post-Assad order.

He’s staying until someone puts a bullet in his head or until the regional equation changes and this won’t happen until a nuclear deal is reached, said the Arab diplomat.

Another diplomat with close links to Assad admitted that the president, 48, is the man of the moment but not the future.

He’s not perfect, and he could be more flexible on humanitarian issues. Besides, he won’t be around forever, and Syria will eventually move forward. But for now, he’s the better of the two choices, the diplomat said.

But die-hard loyalists close to Iran strongly believe Tehran will stand by its friend, whose alliance is a vital land bridge giving the non-Arab Persian state access to Hezbollah, its proxy militia fighting Israel from Lebanon.

God forbid when his situation was worse than this, the Iranians did not give him up, they won’t now.

(Additional reporting by a correspondent in Damascus and Dominic Evans in Beirut; editing by Janet McBride)