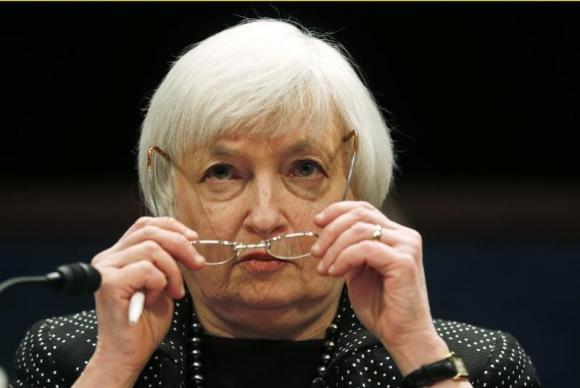

(Reuters) – Janet Yellen’s premium on consensus may lead to a Federal Reserve decision the chair hasn’t yet endorsed, as a near majority aligns in favor of a possible June interest rate hike.

Seven of the Fed’s current 17 members have now said they at least want the option of a June tightening on the table, or have pushed in general for an earlier increase amid an expectation that wages and inflation will turn higher.

By contrast, there’s a dwindling core of officials who say publicly that the economy and labor markets in particular still have a long way to go — only four Fed members have in recent weeks clearly said that rate hikes won’t be appropriate until much later in the year or even into 2016.

The five members of the Fed’s Washington-based board of governors, including Yellen, have spoken less definitively, though governors including Jerome Powell have said they expected strong job growth to continue. Not all of the seven who point to June vote this year on the Fed’s ten-member policy setting committee, but all participate in policy discussions.

The Fed is likely at its March 17th and 18th policy meeting to remove language saying the central bank will take a patient approach to raising rates, taking away the final verbal constraint to a June rate hike, current and former Fed officials say.

It’s likely they remove ‘patient’ in March, said David Stockton, a former Fed research director now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Even if Yellen might not, left to her own devices, be ready to move on rates, there is probably a growing sentiment that the time is getting closer.

The use of the word patient signals that the Fed would wait at least two more meetings before considering a rate hike. There will be one more Fed meeting, in April, before June. If the Fed later this month says it remains patient, then a June increase is off the table, likely pushing the decision to September when the Fed is scheduled to hold a press conference after its meeting.

Stockton said he personally expects a September liftoff. But he regards it as a close call that could shift to June if either wages or inflation begin to firm or if the Fed feels it needs to show markets it can tighten policy.

There is little difference between a June or September start to a tightening cycle that is likely to evolve slowly over the next two years, and maybe you just get it out of the way, said Jon Faust, a Johns Hopkins University economics professor and former special adviser to the Fed board.

The Fed hasn’t raised interest rates since 2006, and Yellen’s career-long focus on labor markets has led some including Stockton to say she would resist an early rate increase, risking higher inflation in favor of trying to generate more jobs. Investors have generally expected the Fed to be later in its first rate hike and to move more slowly than policymakers have indicated.

Data on Fed funds futures contracts collected by CME Group’s Fedwatch have shifted between September and October over the past week as the likely month of the Fed’s initial increase.

A YEAR AT YELLEN’S FED

Yellen has been arguably laying the groundwork for considering a rate hike through changes to the Fed’s policy statement during her first year in office.

Since she took over in February 2014, the Fed has stripped the document of an out of date unemployment target, removed references to a bond buying program as it wound to a close, and ditched the commitment that there would be a considerable time before a rate increase.

Still, the Fed’s job is to promote job growth and control inflation, and there is no inflation. U.S. data have slipped further from the Fed’s two percent target, and some policymakers want more confidence inflation will rise before changing the fed funds rate.

Small data points could make a difference: U.S. core prices ticked up last week even as the fall in energy costs drove the overall inflation rate lower, an outcome likely to reassure Fed officials who consider oil’s impact to be transitory.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (WMT.N) and other major retailers’ decision to raise starting wages is a good sign, and the type of evidence she expects to accumulate as the economy improves, Yellen told a House committee last week

Those and other positive developments have been emphasized by the Fed officials who have honed in on June.

Historically, there is weight on their side: the current near zero interest rate for overnight federal funds borrowing by banks is out of line with the 5.7 percent unemployment rate, inconsistent with many of the formulas used to help set central bank policy, and is even below the minimal levels maintained during recessions, said Standard & Poor’s chief U.S. economist Beth Ann Bovino.

They want to let go of the balloon and see how markets respond, said Bovino, who said the Fed would want to close out years at the zero lower bound and see how a new set of tools for controlling rates works in practice.

(Reporting by Howard Schneider and Ann Saphir, editing by David Chance and John Pickering)