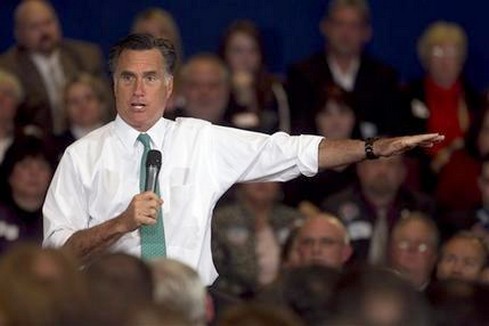

By STEVEN R. HURST

Associated

Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — Mitt Romney wants the United States to get much tougher with Iran and to end what a top

adviser calls President Barack Obama’s “Mother, may I?” consensus-seeking foreign policy.

With the presidential nomination all but locked up, an examination of Romney’s foreign policy

pronouncements and the team advising him on those issues indicates Americans and the world might expect a Republican campaign

that reprises the hawkish and often unilateral foreign policy prescriptions that guided Ronald Reagan and George W.

Bush.

“The world is better off when the United States takes the lead. We should not be playing `Mother, may I?’ about

sanctions on Iran and relations with China and Russia,” said Richard Williamson, a top Romney foreign policy adviser. He has

advised presidents beginning with Reagan, held many diplomatic posts in past Republican administrations and was Bush’s

special envoy to Sudan.

The hot partisan fight over the economy so far has overshadowed Romney’s grievances with the

Obama foreign policy. And polls show the longer the former Massachusetts governor can stay away from a detailed debate on

international affairs, the better it may be for his candidacy.

The most recent Washington Post-ABC News survey found

that Americans trust Obama over Romney on international affairs, 53 percent to 36 percent. For Americans still gun-shy after

the difficult war in Iraq and eager to be done with the prolonged and messy fight in Afghanistan – both conflicts started

under Bush – Romney’s hawkish-sounding policies could prove damaging in the November election.

Even so, Romney will

campaign, Williamson said, as the man who can return the United States to a country that ensures “peace through strength

rather than just managing the gradual decline of our military strength.”

Romney is particularly harsh on Obama’s

handling of Iran and concerns it may be building a nuclear weapon. The president is clearly trying to head off a threatened

Israeli attack on Iranian nuclear installations.

While Obama has not ruled out a U.S. attack, he has not been as

directly threatening as Romney, who positions himself much closer to Israel and hardline Prime Minister Benjamin

Netanyahu.

In one Republican debate, Romney said: “If we re-elect Barack Obama, Iran will have a nuclear weapon. And

if we elect Mitt Romney, if you elect me as the next president, they will not have a nuclear weapon.”

Williamson

downplayed positive news about the Iran nuclear program that came out of a weekend meeting in Istanbul. After that session,

Iran and the world’s big powers hailed the first nuclear meeting in more than a year as a key step toward further

negotiations.

More talks are slated May 23 in Baghdad as interlocutors try to ease international fears that Tehran may

weaponize its nuclear program.

Late last month, after Obama was overheard telling Russian Prime Minister Dmitry

Medvedev that he would have more flexibility in arms control talks after the November election, 36 members of the Romney

foreign policy team wrote to Obama. They said the president’s remarks raise questions about his policies on not just Iran

but also missile defense, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Iraq and Afghanistan, former Cuban leader Fidel Castro,

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and the U.S. defense budget.

Those all are topics that cause reflexive concern among

the most conservative American voters.

The questions, built on shaky assumptions, asked Obama if, for example,

postelection flexibility “would lead you to impose even deeper cuts that will cripple our military?” Or would it “lead you to

undermine Israel further?” And would it “lead you to abandon completely American commitments (in Iraq and Afghanistan),

notwithstanding the enormous sacrifices America forces have made, and with little regard for our national

security?”

Signers of the clearly political letter included Williamson, former Missouri Sen. Jim Talent, former

Minnesota Sen. Norm Coleman, North Korea expert Mitchell Reiss, who was director of policy planning under Secretary of State

Colin Powell, and John Bolton, Bush’s ultraconservative ambassador to the United Nations.

The gloves have definitely

come off. But does that mean a Romney presidency would represent a return to the go-it-alone tactics of the last Bush

administration?

Aaron David Miller doubts that will happen. He is a Wilson Center scholar who served as a Mideast

peace negotiator under Republican and Democratic presidents dating to 1978.

“Romney will inherit the same cruel and

unforgiving world that Obama is dealing with,” Miller said. “He will have to deal with a broken Congress and the changing

nature of the world, which is less amenable to the projection of U.S. economic and military power. He can protest otherwise

in the campaign, but he would be just as risk-averse as Obama, or even more so.”

Romney’s complaints against the

Obama foreign policy have already led him into dicey territory and the chance of making enemies. He recently said Russia is

the United States’ “No. 1 geopolitical foe.” And he promised to slap China with challenges under World Trade Organization

rules as a “currency manipulator.”

Miller lays that all to campaign rhetoric and predicts it is not a prelude to a

Bush-like foreign policy.

“Barring an extraordinary event like Sept. 11, Romney will be much more moderate, much less

reckless than George W. Bush,” Miller said. “Most presidents govern from the center. Bush was an aberration because the

circumstances were aberrant.”

Besides, Williamson said in an earlier interview, “other governments are not naive, and

they understand the rough-and-tumble of U.S. politics just as we understand the rough-and-tumble of politics in other

countries.”