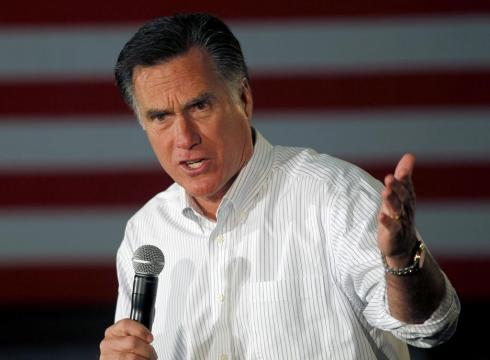

As Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum campaigned in Oklahoma on Thursday, he ripped his rival Mitt Romney for “serially tearing down opponents without offering any kind of vision for what he wants to do for this country.”

Santorum’s lament has already been sung — with encores — by former House speaker Newt Gingrich, who has twice been on the receiving end of millions of dollars of attack advertising from Romney and his supporters. Now, however, it’s not just Romney’s rivals who are saying Romney is all negative, all the time. As he trains his sights on Santorum, he faces increasing complaints that his focus on rubbishing his opponents, successfully, is coming at the expense of a compelling message and his own appeal to voters.

The Romney campaign began pointing the dagger at Santorum immediately after an embarrassing loss in three state contests Tuesday, when Romney began tagging Santorum as a Republican who had helped the party “lose its way” by “spending too much, borrowing too much, and earmarking too much.” Santorum and Gingrich “are the very Republicans who acted like Democrats” when it came to spending in Congress, he said.

The Romney campaign held a conference call Thursday to criticize Santorum for getting earmarked funds for Pennsylvania when he was senator.

“Rick went to Washington — and he never came back,” is the banner on Romney campaign e-mails.

Romney has been taken to task by TheWall Street Journal editorial page, which said he “isn’t winning friends with his relentlessly negative campaign” and “needs … to make a better, positive case for his candidacy beyond his business résumé.”

“This week’s results show that Romney has convinced conservatives that he can convince them that someone else is a bad choice,” says Dan Schnur, who headed John McCain’s 2000 campaign and is now director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California. “But he hasn’t yet convinced them that he’d be a good choice.”

Romney’s attacks from the stump, on television, and supplemented by the pro-Romney super PAC, Restore our Future, have been effective. And the volatile swings of the nominating process mean that voters have seen those tactics repeated.

When Texas Gov. Rick Perry jumped into the race, Romney hammered him on immigration. When Gingrich surged in the polls in Iowa, Restore Our Future ran hundreds of TV ads pounding on the former speaker, and Romney finished far ahead of Gingrich. After Gingrich won South Carolina, the campaign and the super PAC ran ads lambasting him in Florida, where the former Massachusetts governor won.

Negative ads work — but at a cost, Schnur says. Voters can end up loathing the attacker as much or more as the person being attacked.

“It is a danger” for Romney, Schnur says.

“The criticism of Romney is not so much that he’s gone negative, but that when he gets into trouble, he over-relies on that approach to the point that voters don’t hear the more positive messages.”

In opinion surveys, Romney does seem to be losing friends: In a Washington Post/ABC poll taken Jan. 18-22, before the Florida primary, Romney was seen unfavorably by 49% of voters compared with 31% who saw him favorably, a big swing from the 39% favorable, 34% unfavorable rating for Romney in the same poll taken two weeks before.

“He needs to increase the appeal of his own candidacy and his own brand,”‘ says Donna Brazile, a Democratic political strategist-turned-CNN analyst. “The cumulative effect of these negative ads is it’s not only … disintegrating his opponents, but it’s also hurting his image. It’s very difficult to sustain (the message that) ‘I’m a businessman, I’m Mr Fixit’… when the other part they’ve seen is you’re also the guy who is demolishing and demagoguing your opponents.”

In Michigan, which holds its primary Feb. 28 along with Arizona, Romney’s attacks on his opponents won’t be a problem, says Greg McNeilly, a Republican strategist. Voters there expect that “if you believe you’re better than somebody else, you try to punch the other guy out.”

A bigger danger, he says, is that while Michigan voters know the Romney family well — Romney grew up there and his father was governor — they don’t necessarily know what Mitt Romney wants to do to solve their economic problems. “They know who he is and what he’s about. What is missing is if you stopped Republican voters on the street and said, ‘What is Mitt Romney going to do policy-wise?’ that they’d be able to give you a succinct response. That’s his challenge.”

Come fall, voters need to know what Romney — or any Republican nominee — is offering besides the end of Obama’s presidency, Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., said Thursday on MSNBC.

“We need to run on a very specific bold agenda and have an affirming election. If we just run against Barack Obama on the economy and how much we don’t like him and his policies, that’s not enough.”

Brazile, the Democrat, agrees. “What they’re hearing from the Republicans is ‘We dislike President Obama,’ ” she says. “That’ll get you a lot of votes, but that won’t get you across the proverbial finish line.”