(Reuters) – Republican U.S. Representative Paul Ryan’s budget-cutting vision has made him a hero to conservatives across the country. It’s less popular in his hometown.

As Ryan’s proposal to slash taxes and spending started to move through Congress last week, local officials in this humble Rust Belt city scrambled to recover from last year’s cutbacks.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development had clawed back $344,000 from the city’s affordable-housing fund, so the Janesville Community Development Authority voted to drain its reserves to keep its 525 families in the program.

The city won’t have to put anybody out on the street, probably. But there is no cushion left.

Ryan has called for belt-tightening to head off fiscal disaster in the years to come, but Janesville is already familiar with austerity.

There’s less money for job training, health clinics and the food bank; higher property taxes and higher car fees; larger school class sizes, crumbling roads, fewer firefighters.

“It’s like being in a fight against five or six people. Every time you turn around you’re getting punched from a different direction,” said City Council President Russ Steeber.

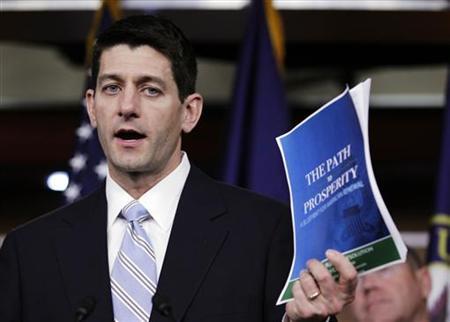

In the 14 years since voters in the southeast corner of Wisconsin first sent him to Congress, Ryan has emerged as perhaps the country’s foremost fiscal conservative. Only 42, he is frequently mentioned as a possible vice presidential pick.

His latest budget plan, unveiled Tuesday, will serve as a rallying cry for Republicans as they try to win control of the White House and both chambers of Congress in the November 6 elections.

Democrats hope voters will be spooked by Ryan’s proposal to partially privatize Medicare, the popular health plan for retirees.

“When people sent Paul Ryan to Washington, D.C., they certainly didn’t send him there to end Medicare,” said Democrat Rob Zerban, who hopes to unseat Ryan in the fall.

Ryan’s district, which encompasses struggling cities as well as affluent lake resorts and blue-collar Milwaukee suburbs, has grown more Democratic in recent years.

Though voters here backed Democrat Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential election, Ryan has continued to win re-election by wide margins and Democratic officials say it will be a challenge to unseat him this year. The Cook Political Report, a nonpartisan tip sheet, rates the race “solidly Republican.”

CLOSE TIES

Ryan has maintained close ties to this city of 60,000 even as his national celebrity has grown. He returns most weekends to spend time with his wife and three young children and local leaders say they see him regularly out and about.

“He is extremely plugged in,” said John Beckford, president of Forward Janesville, a local business group. As in Washington, he is widely admired for tackling the country’s long-term debt.

Though Democrats have hammered Ryan on Medicare and tax cuts that would benefit the wealthy, they have devoted less attention to other proposed spending cuts.

Under Ryan’s plan, the government would spend $3 trillion less than Obama over the coming 10 years on domestic programs. That’s one-third less for Medicaid, the health plan for the poor; one-quarter less for transportation, and one-third less for education. Tax breaks and food and housing assistance for the poor would shrink by 16 percent.

His budget, like the rival vision outlined by Obama in February, has no chance of becoming law as long as Democrats and Republicans split power. But no matter who controls Washington after the November elections, continued austerity is likely to be the rule under a 10-year, $1 trillion deficit-reduction plan passed last year.

Even relatively modest reductions hit hard in Janesville, which is still digging out from the closure of a General Motors plant four years ago that left 4,000 people out of work.

Businesses are pushing to widen Interstate 90, an effort that would rely on federal money. Southern Wisconsin Regional Airport also is counting on federal dollars in the next 10 years to cover 90 percent of a planned $5 million runway upgrade.

Federal job training grants helped many of the laid-off GM workers learn new skills at Blackhawk Technical College, and one in five students there currently rely on federal student loans or grants, according to a school official.

Ryan’s proposed Medicaid cuts would strain local hospitals, which already lose money on every patient they see under the program.

“Our mission is to provide health services to the communities where we have a presence,” said Rich Gruber, a vice president at Mercy Health System. “If I don’t have a financial margin, I’m never going to be able to accomplish that mission.”

Janesville was hammered by the 2008-2009 recession. The GM plant closure sent shock waves through the ecosystem of parts suppliers and other employers that depended on the massive facility for business.

Food banks and other local charities struggled to keep up as demand swelled and private donations plummeted. The city’s rental-assistance program, funded by federal money, stopped accepting new applicants two years ago.

Things are looking up lately. The unemployment rate has fallen to 8.3 percent, still well above the statewide average but well below the March 2009 peak of 13.9 percent. A startup company recently announced plans to build an $80 million medical-isotope plant, and hospitals are expanding.

Advertisement

DIGGING OUT

Still, enormous challenges remain as families struggle to climb back into the middle class.

One in 25 school children was homeless at some point last year, and half qualify for free or reduced lunches. Manufacturers are hiring again, but many of the jobs pay $9 per hour, far short of the $20 to $30 hourly wage paid by GM.

Many workers don’t have the communications or math skills that better-paying jobs demand, and federal job training funds are projected to shrink 6 percent to 12 percent in the coming fiscal year. There are 8,000 fewer jobs now than there were a decade ago.

“At one point in time I probably would have said we need to scale back government. Now I see people that are at a loss, they don’t know where to turn,” said Robert Borremans, the head of the Southwest Wisconsin Workforce Development Board, which oversees job-training efforts in Janesville.

Not everyone shares this view. Several local business leaders said they agreed with Ryan’s argument that lower taxes and fewer regulations, rather than continued federal spending, would get the economy moving.

Bill Sodemann had to lay off half of his employees at his telecommunications firm during the height of the recession. As head of the Janesville school board, he’s made painful decisions there as well.

The school district had to cut 110 of its 1,400 staff positions last year, raise class sizes and hike fees for high school sports after the state legislature slashed its contribution. More painful cuts loom next year.

‘LIKE A DRUG DEALER’

Federal contributions also fell last year by 33 percent as stimulus money dried up. Sodemann says the burst of federal money only postponed the district’s day of reckoning.

“They give you money and hook you on a program and say, ‘OK, now it’s gone, you fend for it,” he said. “It’s kind of like a drug dealer, I guess.”

Sodemann points to a new pre-kindergarten program as an additional drain on resources. Parents who want to put their kids in the program should pay for it themselves, he said.

“Just because it’s beneficial doesn’t mean government should pay for it,” he said.

Several miles south of Sodemann’s downtown office, 4-year-old children enrolled in the program stream off a playground into a cheery day-care facility run by a nonprofit group, Community Action Inc.

Early-childhood programs like these have been shown to boost school performance and reduce crime. Federal subsidies cover more than two-thirds of the program, which allows parents to enter the workforce rather than remain at home and mired in poverty, nonprofit officials say.

Community Action officials choose their words carefully when asked about Ryan. He’s willing to listen to their concerns, they say, even as he makes clear that his focus is on federal fiscal issues rather than the immediate needs of his community.

“It’s a question that doesn’t come to the top of his list,” said Lisa Forseth, Community Action’s executive director.

Donna Hays, a nurse practitioner who runs the nonprofit’s women’s health center, is more direct as she puts on her lab coat and stethoscope.

“We sometimes have to ask him if he remembers where he came from,” Hays said.

(This story is refiled to drop extraneous word “percent” in 17th paragraph; rephrases 39th paragraph)

(Editing by Alistair Bell, Vicki Allen and Bill Trott)