(Reuters) – During an informative and entertaining

address to an anti-doping conference last month, German researcher Mario Thevis referred to “80, 90, 100” new

performance-enhancing drugs for which no tests yet exist.

“They act like EPO (erythropietin) but they are structurally different and that means the current EPO

tests will not pick them up,” he told delegates to the conference in London convened by worldsportslawreport.

Thevis

added that “according to anecdotal evidence and rumors” the drugs, which replicate EPO’s blood-boosting qualities, were

already used in elite sports.

EPO stimulates the bone marrow to produce more red blood cells. This increases the

oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, allowing muscles to perform for longer.

News that up to 100 new drugs could be

available in the runup to this year’s London Olympics will astonish only the naive.

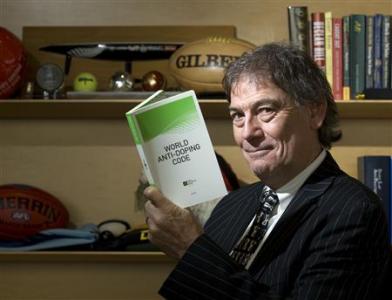

“It doesn’t surprise

me,” responded World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) director-general David Howman. “We are in the area where we are into third and

fourth generations and they continue to climb. Whether they are detectable or not depends on the ability of the individual

laboratory.”

One in two competitors will be tested during the London Games, including all medalists, and the estimated

400 daily tests are higher than any previous Olympics.

The problem will not be at the Games themselves, running from

July 27-August 12, but the months before in the eternal cat-and-mouse game between the dope cheats and the

testers.

“In terms of the program that is in place for the Olympic Games, I think it is very good,” Howman said in a

telephone interview with Reuters from WADA’s Montreal headquarters.

“The International Olympic Committee have got

probably the most extensive program they could possibly operate. From the day that athletes come into the opening of the

village to the closing ceremony, that’s good.

“What we need is extensive pre-Games testing and we need all the

samples that are collected to be tested for the full menu of substances.”

SORE SUBJECT

EPO, the drug at the

core of the 1998 Tour de France doping

scandals, is a sore subject for WADA.

Earlier this year, Howman said that out of 258,000 doping tests conducted in

2010 only 36 had turned up positives for EPO.

“You can understand the frustration that I have been voicing over the

past six months,” he said in the interview. “We can do a little bit better than that and one of the reasons we don’t do

better is that many of the samples are sent to the lab and the lab is asked not to analyze for EPO. That’s just

outrageous.”

Howman said there were a number of reasons why national anti-doping agencies or international federations

did not want samples analyzed for EPO.

“One, we don’t want to pay the extra cost for EPO, two we don’t think we have

a problem in our sport and three, maybe, is we don’t want to know what the results are going to be,” he said.

“What

we are getting is many, many samples not being analyzed. That’s our suspicion that there were only 36 positive tests in

2010…that defies logic.”

Another current headache for the testers is gene doping, the use of gene therapy to smuggle

performance-enhancing drugs into a healthy body. Legitimate gene therapy introduces genes into the body to treat

diseases.

Gene doping was included on WADA’s prohibited list in 2003 and in 2006 years former WADA president Dick

Pound said: “You would have to be blind not to see that the next generation of doping will be genetic.” However, six years

later there is still no test and there will be nothing in place at the London Games.

“DIFFICULT TO DETECT”

Anna

Baoutina, a senior research scientist at the National Measurement Institute in Sydney, told Reuters effective methods are

being devised but it was up to WADA to decide when they are to be implemented.

“The major feature of gene doping is

that it is very difficult to detect compared to drug doping,” she said.

“In effect, gene doping is the

‘illegitimate’ derivation of gene therapy. Gene therapy aims to treat human diseases which are caused by defects in genes.

It does this by introducing in the cells of our bodies new genetic material.

“Gene doping is also the introduction of

genetic material into the cells but in the absence of defective genes and with the purpose of enhancing performance. For

example, if additional copies of genes for human growth hormone (HGH) or EPO are delivered into athletes’ cells, the cells

will produce more of these proteins and this may result in performance enhancement.”

Baoutina said EPO was likely to

be among the first candidates for gene doping.

“The problem is that the doping gene and the protein that is produced

from it are very similar to the natural forms that are present in the body,” she said.

Could gene doing be a problem

in London?

“Scientists working on gene doping detection may be close to a method of testing for gene doping soon,”

Baoutina said. “In the meantime, the IOC decision to store the athletes’ samples for eight years may be a disincentive for

them and their managers to try gene doping.”

Howman said he rated gene doping alongside a number of other threats

resulting from advances in medicine and health. He added he had been told 25 percent of the world’s pharmaceutical products

came from the black market.

“You need to look at HGH and testosterone, you need to look at the 40-odd varieties of

EPO,” he said.

“And then you need to look at the ways and means some of these substances are used in micro-dosing or

cocktails and so on mostly in an effort to avoid detection.

“That’s what you are dealing with, you are dealing with

people who are very sophisticated and have devised the art of being sophisticated in order to avoid detection.

“It’s

a little bit like (what) tax lawyers and accountants do to avoid people paying tax. The same sort of sophistication in a

different part of society.

“This is the difficulty when you get medicine advancing through the pharmaceutical industry

in secrecy because they don’t want their research and development to be done by other pharmacies and so on.

“On the

other side of the coin, is the black market. They put stuff out there before it has been properly regulated and approved

ethically. So you have a black market where I am told 25 percent of the world’s pharmaceutical products come

from.

“We just have to rely on information and pass it on to people who can do something about it.”

(Editing by